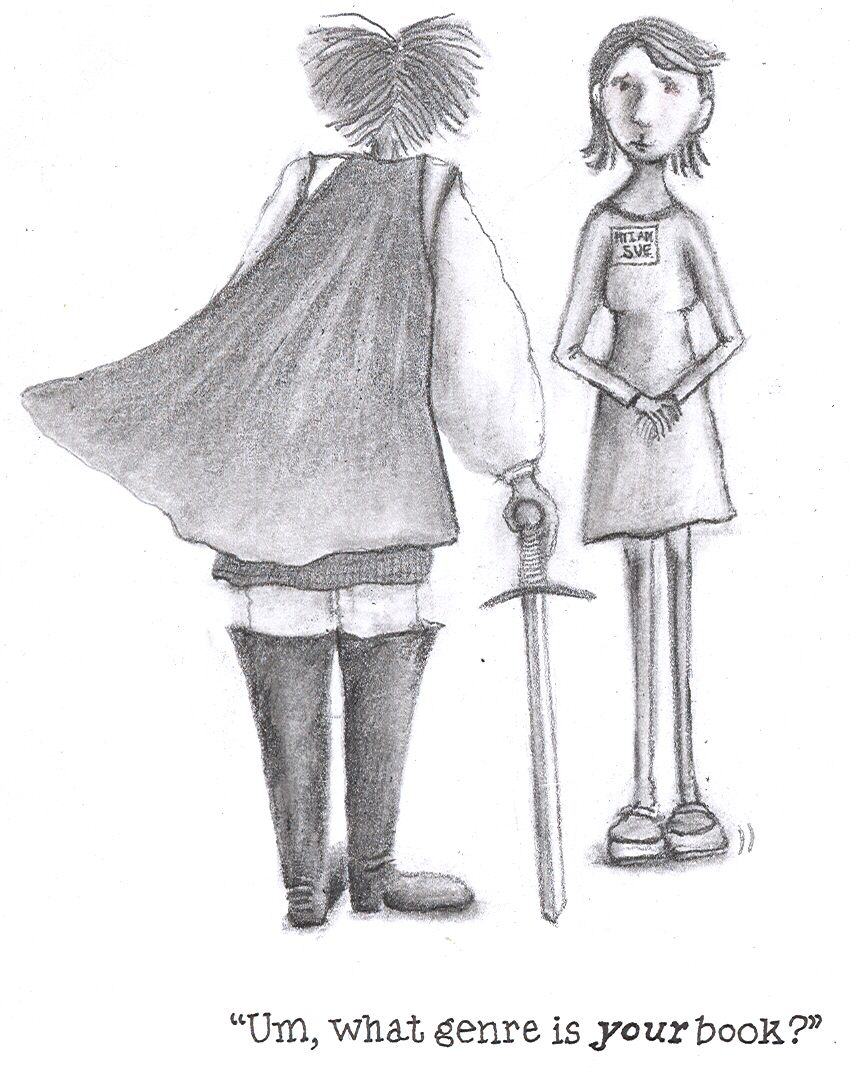

Genre: A Glorious Concept

by James Thayer

Illustration by Jennifer Paros - Copyright 2009

Before he began writing The Chronicles of Narnia, C.S. Lewis told his friend J.R.R. Tolkien that “there is too little of what we really like in stories. I am afraid we shall have to try to write some ourselves.”

What do readers like in a novel? Reliable entertainment. Most book buyers already know the kind of story they are looking for before they begin to browse. They want a certain category, a story with a particular content that has entertained them in the past. In other words, a genre novel.

Genre is a loaded word. George V. Higgins and Raymond Chandler despised being labeled genre novelists. But writing a genre novel—more charitably called commercial fiction—has huge advantages.

They sell. Look at the fiction best seller lists, or the best seller table at your neighborhood bookstore. Almost every title fits into a genre. Agents and publishers understand this, and when they look at your query letter or proposal, their first questions are usually, “What is this? How does this fit into the market?”

If they conclude the manuscript is from a new writer who is attempting to break into literature’s fourth dimension, most often your query letter or submission will be rejected out of hand. Agents and editors think in terms of genre because of market necessity. Literary agent Peter Rubie says that the development of genres was “basically to help you more easily find what [the book buying public] is looking for. They are also guides that let you know, generally, what you can expect to find in a certain type of book.” A genre book can make a writer a bestseller. “Breakout novels can be written in any genre,” says literary agent Donald Maass.

Even legendary writers knew that the tried-and-true sells. “It is better to have a permanent income than to be fascinating," Oscar Wilde said.

They endure. Genres aren’t passing fads. Clive Bloom notes that ‘the most popular genres at the end of the twentieth century were virtually the same as at the beginning.”

Virtually anything you want to write is in a genre anyway. “Today any accessible, fast-moving story written in unaffected prose is deemed to be ‘genre fiction,’” says B. R. Myers. We’ve got mainstream, romantic comedy, romance, comedy, detective, thriller, science fiction, fantasy, western, sports, woman’s (also known as chick lit), horror, and historic, and others. Even authors considered America’s preeminent men and women of letters write in a genre called literary fiction.

Excellence is found in genre fiction. Patrick O’Brian wrote thrillers, or perhaps they were historicals. Raymond Chandler wrote detective novels. H.P. Lovecraft wrote horror. J.R.R. Tolkein wrote fantasy. (Lord of the Rings has been called “one of the few twentieth-century novels likely to endure.”) John LeCarre writes thrillers. Edgar Allan Poe not only wrote in all genres, but is said to have invented all of them. If your goal is to enter posterity, writing in a genre will not bar your way.

Writing in a genre does not mean pounding out hack work. B. R. Myers says that “intellectual content can be reconciled with a vigorous, fast-moving plot,” and he gives as examples Budd Schulberg’s What Makes Sammy Run? and John O’Hara’s Appointment in Samarra.

Smart people reads the genres. Writing in a genre will not diminish the quality of your readership. A strong argument can be made that Teddy Roosevelt brought more mental horsepower to the presidency than anyone before or since, and he was an avid reader of dime novels. And among Franklin Roosevelt’s favorite writers was Craig Rice, author of hard-boiled detective novels.

A genre novel is not imitative. Writing in a genre doesn’t mean the writer needs to fear her plot has been done before. It’s all been done before. One school of thought is that there are only five plots (man against man, man against himself, man against nature, man against society, and man against God) and all novels are derivatives of these five. Donald Maass says, “There are certainly no new plots. Not a one. There are also no settings that have not been used, and no professions that have not been given to protagonists.”

Kurt Vonnegut plotted our novel: “Somebody gets into trouble, and then gets out again; somebody loses something and gets it back; somebody is wronged and gets revenge; Cinderella; somebody hits the skids and just goes down, down, down; people fall in love with each other, and a lot of other people get in the way; a virtuous person is falsely accused of sin; a sinful person is believed to be virtuous; a person faces a challenge bravely, and succeeds or fails; a person lies, a person steals, a person kills, a person commits fornication . . . . I guarantee you that no modern story scheme, even plotlessness, will give a reader genuine satisfaction unless one of those old-fashioned plots is smuggled in somewhere.”

So whatever we write, we won’t be the first, and we shouldn’t worry about it. Edith Wharton said the fear of imitation is immature.

We can learn the craft from the genre. Writing in a genre will help plot the novel, and help avoid mistakes that lead to failed manuscripts. All the genres have conventions. Roger Ebert calls them “the ancient story machinery groaning away below the deck” that makes us smile. Readers—and, as a result, agents and editors—are looking for the unexpected, but also the expected.

What is expected in a romance novel, for example? A little research offers a lot of guidance for the writer. The Romance Writers of America say a romance novel is a “love story with an optimistic and emotionally satisfying ending.” Isn’t that great to know in advance of writing? If we write a romance novel where the heroine is in despair at the end, we’ve wasted our time.

But wait. There’s more. Linda Barlow and Jayne Ann Krentz write that “The reader trusts the writer to create and recreate for her a vision of a fictional world that is free of moral ambiguity, a larger-than-life domain in which such ideals as courage, justice, honor, loyalty and love are challenged and upheld.” And Nora Roberts says, “The books are about the celebration of falling in love and emotion and commitment, and all those things we really want.” Paul Gray says that readers do not want a heroine who is “a passive office temp with an eating disorder and the man of her dreams a philandering salesman with a wife and three kids in Cleveland.”

Certain conventions for a genre are specific. For a romance novel Jude Deveraux says, “A lot of new writers come to me and say; ‘I’m going to give the reader two romances in one book’. My response is always: ‘You couldn’t come up with enough plot for one, right, so you’re going to stick a second one in?’ Well, that’s a taboo. People who read romances only care about the hero or heroine.’” Your chosen genre will offer lessons in how to do it right.

Going to write a novel? Pick a genre. The benefits are many. Mark Twain agreed: “My books are water; those of the great geniuses are wine—everybody drinks water.”

James Thayer’s thirteenth novel, The Boxer and the Poet; Something of a Romance, was published by Black Lyon Publishing in March 2008. He teaches novel writing at the University of Washington Extension School, and he runs a freelance editing service (www.thayerediting.com).